By: Samuel Khodadad 12/06/2024

One of the unforeseen consequences of choosing the Near-West side to build the Circle Campus was community’s diversity.

The University found itself an accessible route for a significant portion of first-generation students, many of whom were minorities. The institution was not built to serve these students but mostly nearby suburbanites while having the institution act as a buffer for the Loop: Chicago’s business district.1 When the school was unable and unwilling to change, a group of motivated students and faculty decided to take action.

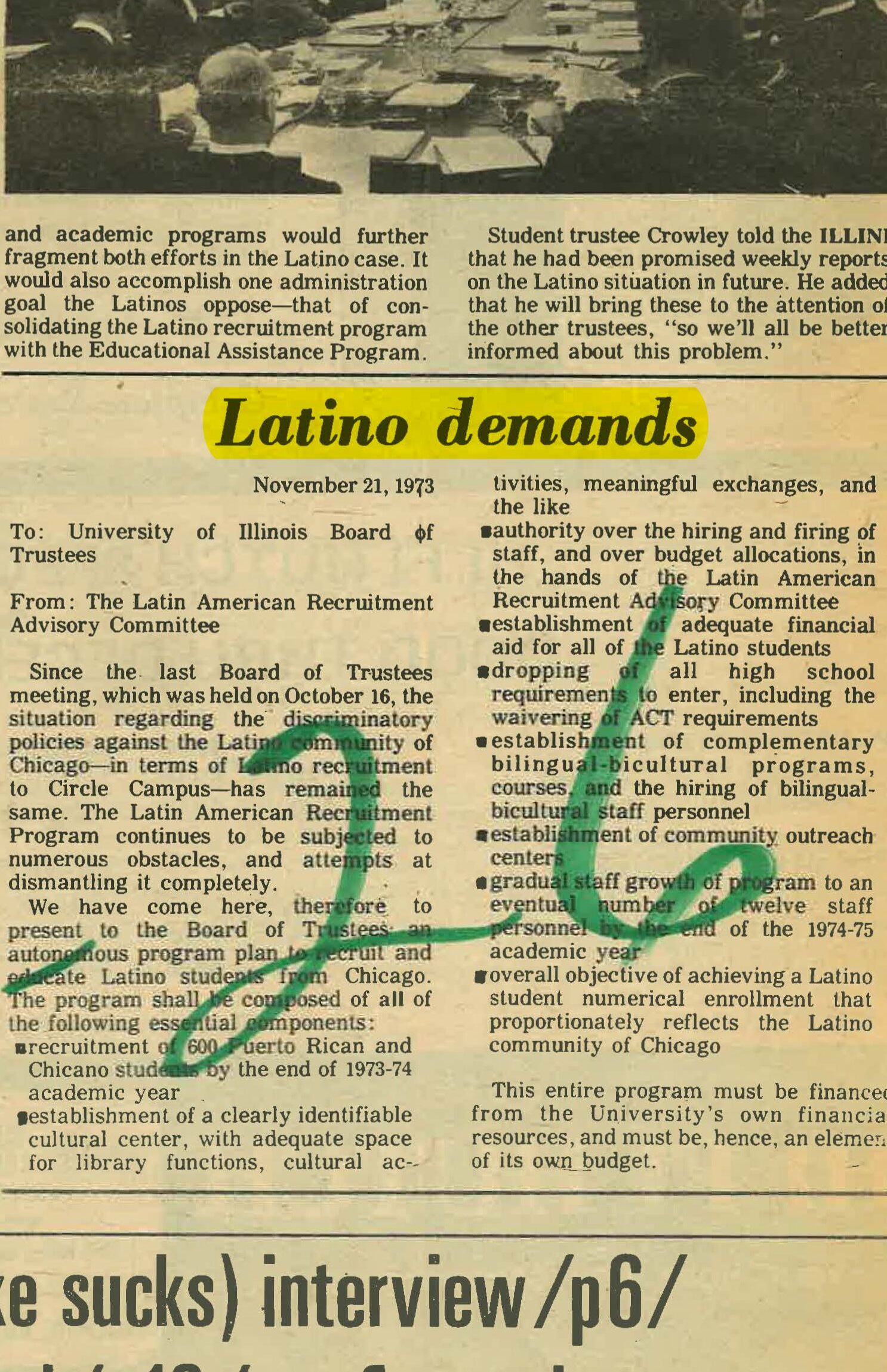

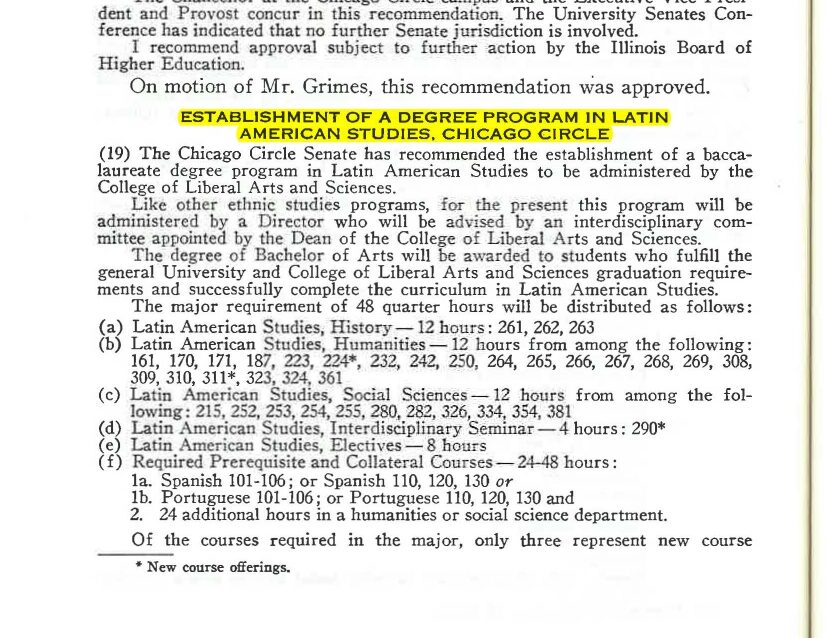

Various students fought to have their cultures recognized in an academic setting. in 1971, the Board of Trustees acquiesced and approved the Latin American Studies program for the 1972 school year.2 This move was not done with support of the student body however, and the newly appointed director of the program was unpopular to the point of continued and additional protest.3

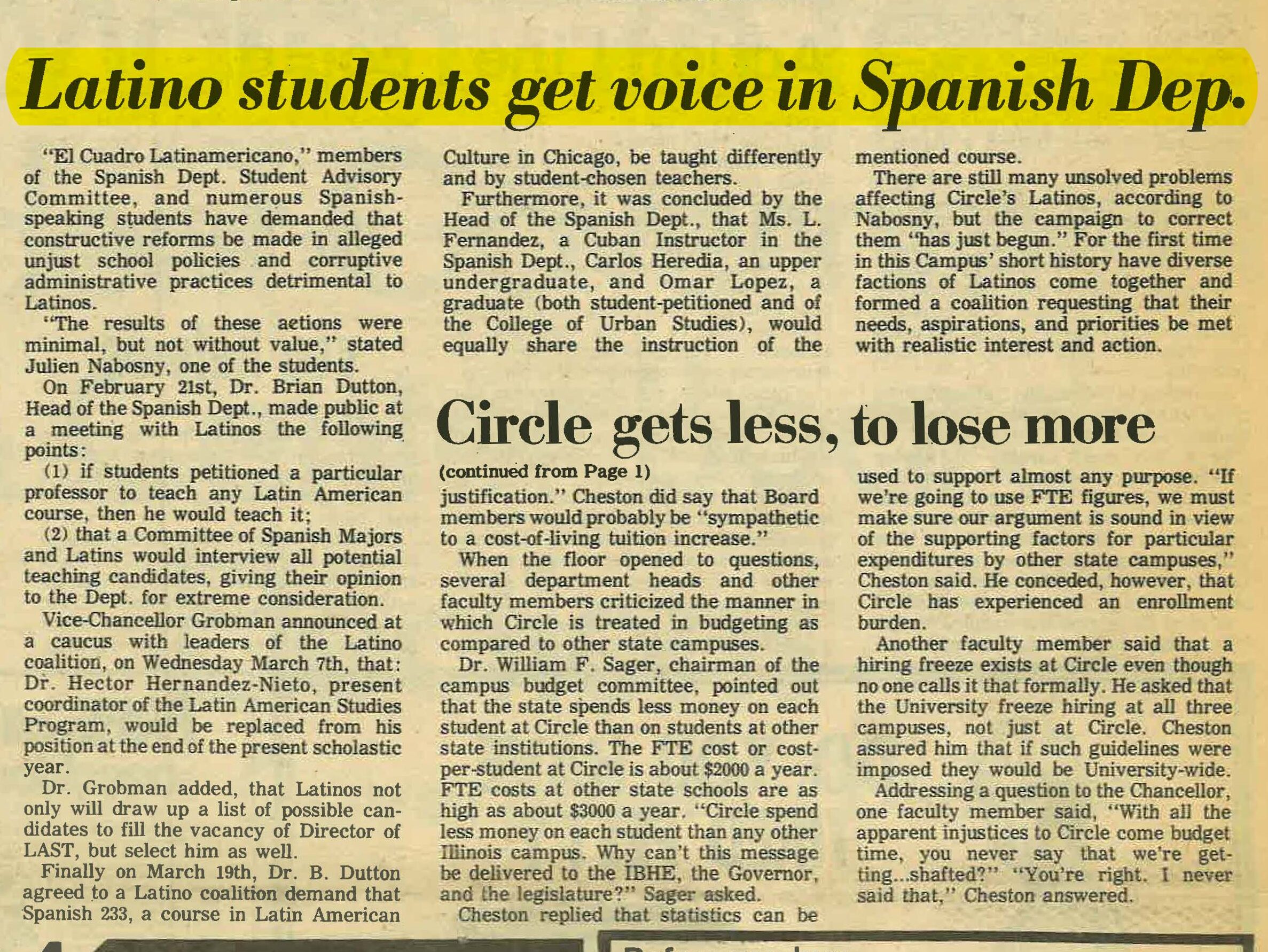

Eventually through protest the administration allowed reforms. Namely, as stated in this University paper the Chicago Illini “Dr. Grobman added, that Latinos not only will draw up a list of possible candidates to fill the vacancy of LAST select him as well.”4 The article mentions the diversity of various Latin American groups that came together to pressure the administration. The student body would eventually present Otto Pikaza,5 a former professor at Roosevelt University in Chicago’s Loop.

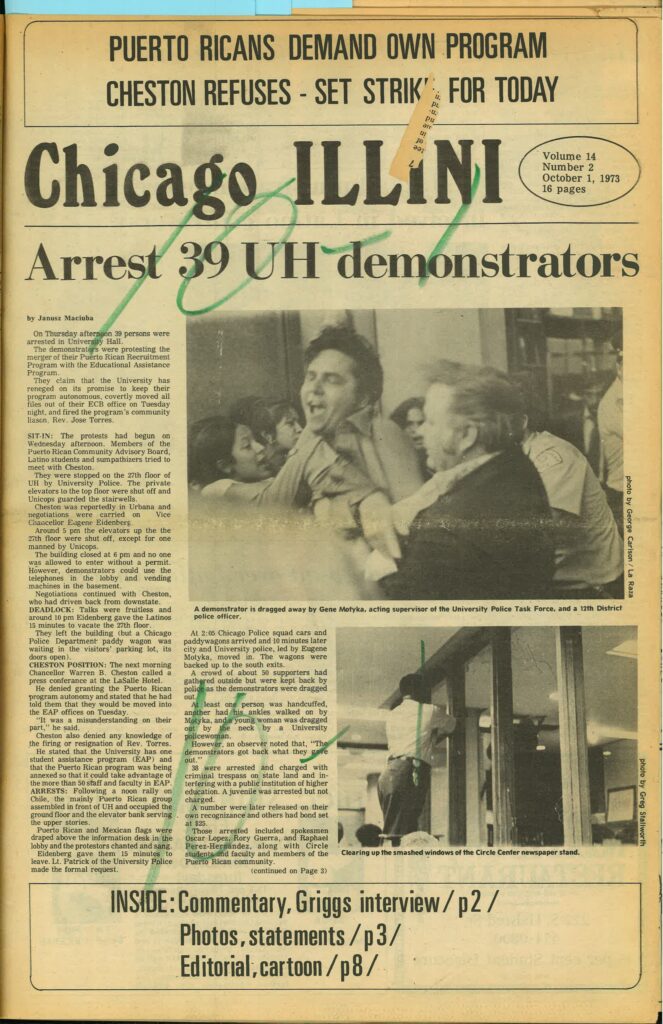

This trend of having to force the arm of administration in order to make any changes to a not-so-veiled status-quo is something that is carried throughout this institution’s history. Another incident occurred around 1973 at University Hall. The Chicago Illini reported on a demonstration to force a meeting with the Chancellor that ended in 39 arrests.6 The protest was arranged after the school announced that the Puerto Rican Assistance Program would be merged with the general Educational Assistance Program. The protestors lamented the new loss of autonomy and lack of representation the change would bring about.

Otto Pikaza himself was sometimes a player in these protests, pictured below is an image from a University Hall sit-in on campus. In his time as director of the Latin American Studies program he also assisted with the creation of two similar but separate and autonomous groups: The Latin American Recruitment and Educational Services (LARES) program which opened in 1975 and The Rafael Cintron Ortiz Cultural Center in 1976. The namesake of the latter was in fact a member of faculty hired by Pikaza.7 Together these three organizations would come to serve the Latin American community at the school for generations and all continue to operate today.

Student Activism was not limited to the 1970s with Latino students. In the 1990s, various incidents on campus targeting the African American student body resulted in an on-campus response that brought headlines. One Chicago Tribune article loudly announced “Racial Incidents at UIC Trigger ’60s-style Protest by Students”8 The incident in question was in regard to primarily verbal harassment and defamatory graffiti experienced by African American students in the University dormitory.9 After yet another unsuccessful town-hall style meeting discussing this and other troubling incidents, several dozen especially determined students marched to James Stukel – the interim chancellor’s office. Stukel was notably missing from the meeting and so the group decided to bring their grievances to him. Eventually this demonstration was able to force a commitment from Stukel to find a permanent site for an Afro-American Cultural Center which would today be known as the Black Cultural Center.10

In fact this protest and demonstration has shaped a large portion of the student experience at the University today. Among the protestors’ 23 demands was including a mandatory course in cultural diversity, deeper recruitment of inner-city students, codification and documentation of racial altercations and minority-impact studies, among other things.10 Today the school has taken up many of these demands and instituted them into university policy. For example, the Nathalie P. Voorhees Center for Neighborhood and Community Improvement, a part of the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs has been monitoring quality of life, gentrification, salaries, and other variables. More recently in 2020 the administration founded the Office of Community Collaboration which was devised to increase cooperation and investment in disenfranchised communities. The student body is still extremely active as well, with some students holding protests for any involvement with the conflict in Israel, hosting rallies, and marches on campus.

Works Cited

Chicago Illini LALS Documents – Click here for various news clippings surrounding the Latino Student body’s fight for equity (Courtesy of UIC LALS).

- Cohen, Adam Seth, and Elizabeth Joel Taylor. American pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley ; his battle for Chicago and the nation. New York: Back Bay Books, 2001.

2. Rep. University of Illinois Board of Trustees Fifty-Sixth Report 1970-1972, n.d.

3. Figliulo, Susan. “Latino Demands.” Chicago Illini, November 26, 1973, Volume 14 , Number 10.

4. “Latino Students Get Voice in Spanish Dep.” Chicago Illini, March 26, 1973.

5. “Latin American and Latino Studies.” Latin American and Latino Studies | University of Illinois Chicago. Accessed December 6, 2024. https://lals.uic.edu/about/history-of-lals-at-uic/.

6. Maciuba, Janusz. “Arrest 39 UH Demonstrators.” Chicago Illini, October 1, 1973, Volume 14 , Number 2.

7. “Rafael Cintrón Ortiz Latino Cultural Center.” Rafael Cintrón Ortiz Latino Cultural Center | University of Illinois Chicago. Accessed December 6, 2024. https://latinocultural.uic.edu/home/rafael-cintron-ortiz/.

8. Chicago Tribune. “Racial Incidents at UIC Trigger `60s-Style Protest by Students.” Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1990. https://www.chicagotribune.com/1990/11/17/racial-incidents-at-uic-trigger-60s-style-protest-by-students/.

9. Chicago Tribune. “Racial Tensions Emerge at UIC.” Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1990. https://www.chicagotribune.com/1990/11/15/racial-tensions-emerge-at-uic/.

10. Chicago Tribune. “UIC Students Press Their Demands.” Chicago Tribune, December 4, 1990. https://www.chicagotribune.com/1990/12/04/uic-students-press-their-demands/.