Department of Urban Renewal Annual Reports 1964 and 1968

Amy Hernandez

The Chicago Department of Urban Renewal was formed in 1962 as a result of the State of Illinois Urban Renewal Consolidation Act of 1961, which required municipalities to create departments of urban renewal that focused on projects relating to land clearance and redevelopment.

In this memo before the official annual report from the Department of Urban Renewal (DUR), John G. Duba, the commissioner of the DUR states the purpose of the department: slum clearance and neighborhood conservation. However, throughout the report it becomes apparent that slum clearance is favored over conservation.

Slum Clearance in Little Italy

Slum clearance, the destruction of “blighted” areas, drastically rose in popularity after the Housing Act of 1942. This act provided local governments with federal funding for redevelopment plans. The combination of federal funding and the power of eminent domain would lead to large scale urban renewal projects that would disrupt communities across the country. The objective of the Housing Act of 1942 was clear — “blight” was contagious and in order to redevelop cities it needed to be stopped.1

In the late 1950s Chicago’s Little Italy neighborhood was designated as a blighted urban renewal site. Residents advocated to have this designation because this meant that they would receive federal funding to tear down buildings and replace them with new and affordable housing. They would not be able to return because the UIC Circle Campus would move in.

Little Italy was already in the process of starting rehabilitation projects which left several buildings already demolished. This, and federal funding would speed up construction and lower costs, which was appealing to stake holders of the university – including Richard J Daley.

“They poured out more Democratic votes than Daley’s own neighborhood”.2 The residents of Little Italy felt betrayed. They gave Daley their unwavering support, and in turn they were deceived.

This is just one neighborhood that was completely unrecognizable once urban renewal projects started. Residents of possible sites of urban renewal do not want to go through with the projects because they’ve seen the destruction that is left behind with all the broken promises of improved infrastructure and affordable housing.

“One of his comments that he’d make was that he loved neighborhoods, and he wanted to keep the city together through its neighborhoods,” she said. “But he really didn’t give a damn about the neighborhoods when push came to shove. If somehow or other you were in the way of his future plans, the neighborhood didn’t matter that much” – Florence Scala3

Projected Plans for Urban Redevelopment 1964 vs. 1968

Urban Renewal Progress

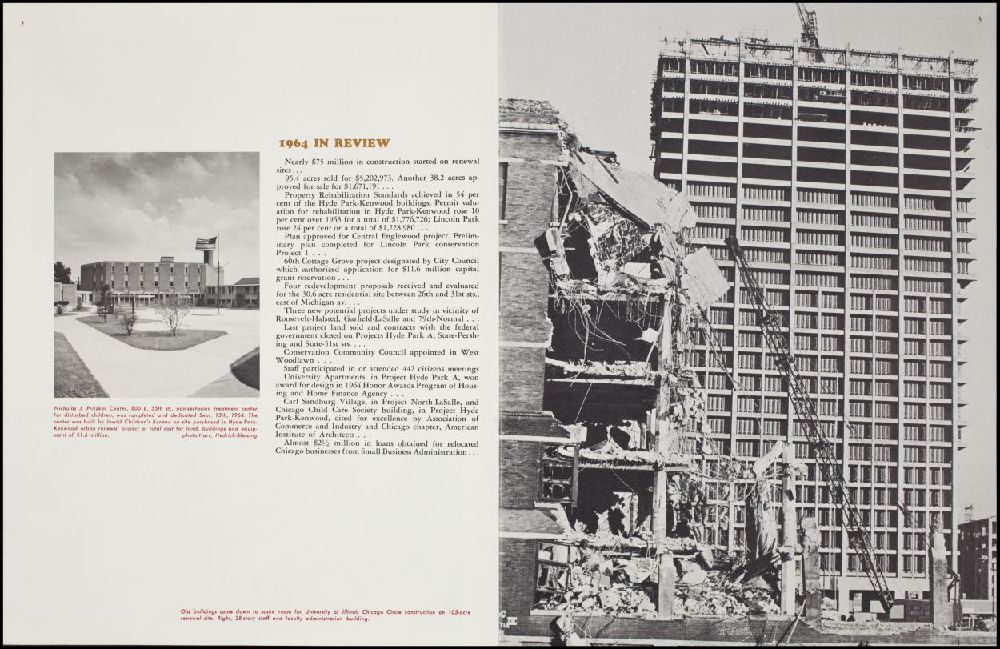

In the Chicago Department of Urban Renewal Annual Report from 1964, they open with the fact that there was nearly $75 million spent on construction in urban renewal sites that year.

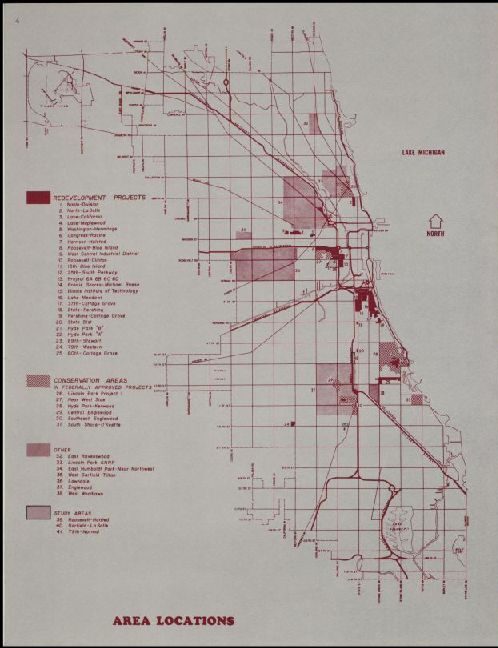

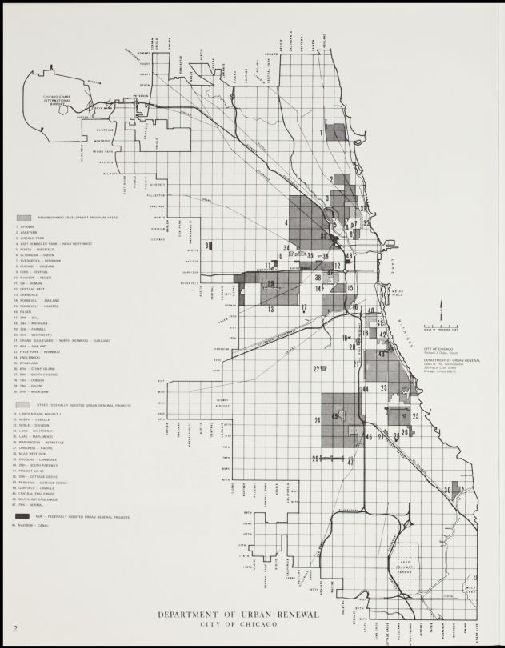

In this report there is a map of proposed sites for urban renewal and they are categorized as redevelopment projects, conservation areas in federally approved projects, other, and study areas. A majority of sites on this map are redevelopment plans, which means slum clearance and demolition will take place if the projects begin.

However, in the annual report from 1968 there are only three categories for a similar map. These categories are: neighborhood development program areas, other federally assisted urban renewal projects, and non-federally assisted urban renewal projects.

In the introduction to the 1968 annual review they also boast about the money being spent and brought in from urban renewal projects, but there was an additional category to their overview of the year — residents and the buildings they occupied.

“During the year the DUR acquired 600 properties, demolished 725 structures, and relocated 2,100 families, 1,100 individuals, and 300 non-residential establishments”4

Expectation vs. Reality

Just looking at the overviews of the annual reports coming from the Department of Urban Renewal shows that demolition and redevelopment were favored. Slum clearance was seen as necessary to stopping “blight” and modernizing cities, but it was at the expense of vulnerable communities. Instead of revitalizing the city as a whole, it tore apart tight-knit communities, leaving targets of urban renewal displaced and without adequate support.

- Collins, William J., and Katharine L. Shester. “Slum Clearance and Urban Renewal in the United States.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5, no. 1 (2013): 239–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43189425. ↩︎

- Royko, Mike. Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago. New York. Plume Publishing, 1988. ↩︎

- Eng, Monica. “Daley Vs. Little Italy”.WBEZ Chicago. https://interactive.wbez.org/curiouscity/littleitaly/ ↩︎

- Urban Renewal, 1968 (Folder IV-1126), Chicago Urban League records, UIC Special Collections, University of Illinois Chicago https://n2t.net/ark:/81984/d3g15tm7r ↩︎