St. George and the Dragon:

The Struggle for the Right to the Near West Side

By Colin Goss

December 06 2024

“[My brother] Ernie became so knowledgeable about how communities work, what the laws are, how the city departments work, the role of local politicians, what role politics play in every facet, he became very knowledgeable. But you see, in a city like this, what good does that knowledge do? You could be St. George and you couldn’t slay that dragon.” – Florence Scala, Near West Side community activist who led the fight against UIC’s construction.1

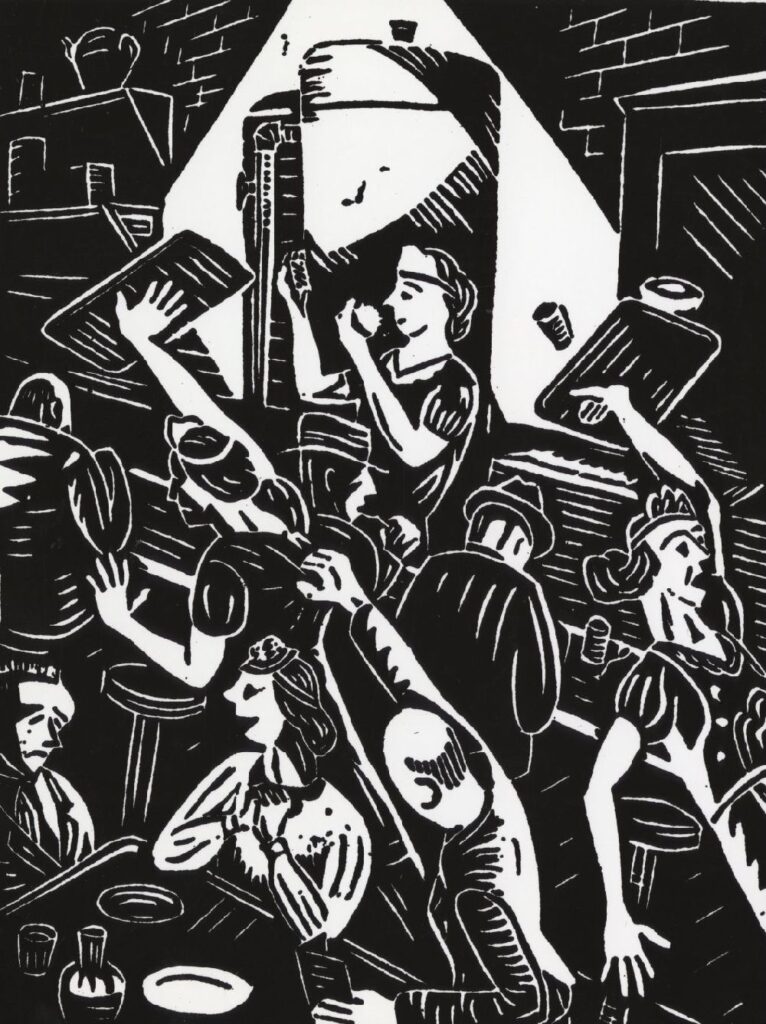

“The rubble creeps up on the last remaining pawn-shops, bodegas and pizzerias, the last remaining small haberdasheries, kafenios and taquerias; Street of zucchini, baklava and enchilada, at last you are falling before the advance of standardization; Street of olives, snails and avocados, your days are numbered; Street of chianti, mazel and retsina, of ouzo, arak and tequila with your guitar thumping cantinas and belly-dancing tavernas, those who do not know you have the power to destroy you for behold advancing in the distance following in the wake of the bulldozers and rising above the clouds of dust of your corpse are your brand new tombstones called civic redevelopment; human anthills that look like a combination of cell-block and skyscraper, yes they are building bigger and better tenements that are destined to become bigger and blightier areas. And you, you good city planners and you fat pocket contractors, when your job is completed and you come down here to look at your accomplishments, are you honestly going to believe you’ve made any improvement other than in the health of your back pockets?”

– Carlos Cortez, excerpt from his poem “Requiem For a Street”, about the demolition of the Near West Side

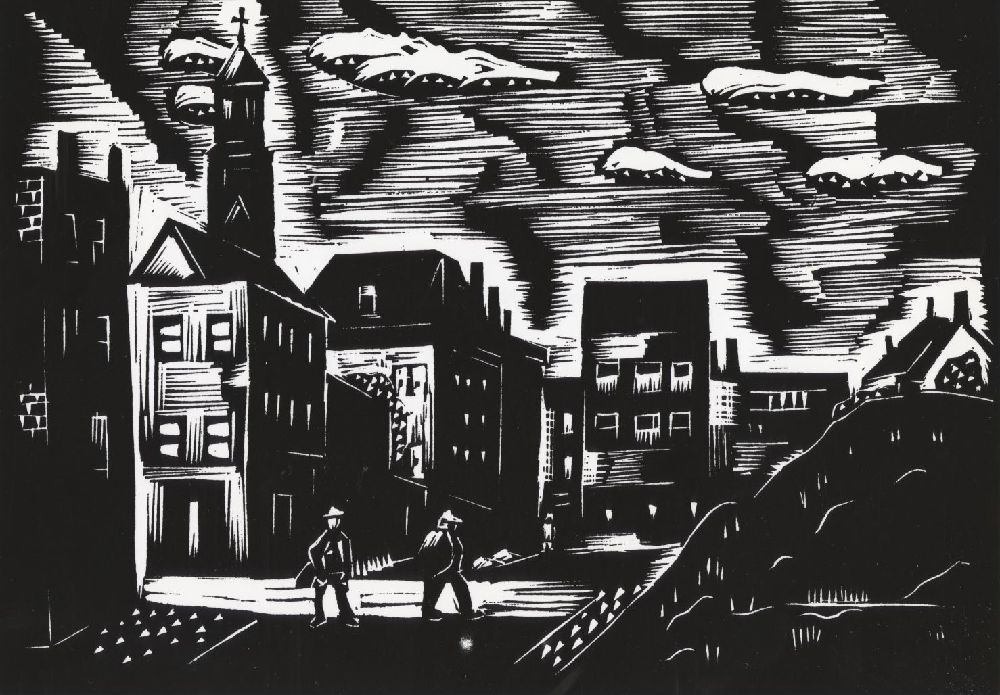

The construction of the University of Illinois expansion campus in Chicago on a 55 acre tract of land in the heart of the Near West Side- one of the city’s oldest, densest, and most diverse immigrant neighborhoods- was the result of a complex and layered struggle between a working class community against the combined gargantuan force of the University of Illinois, the Daley Machine, and the city’s business elite. One way in which the struggle for the Near West Side could be characterized is as a struggle for the right to place; one ultimately revealing a hierarchy in the distribution of space which not only prioritizes the interests of the business and political elite, but also dominates and dispossesses working class communities.

Richard J. Daley’s work to secure a University of Illinois expansion campus within the city limits of Chicago dates back to his time as a state senator where, in 1945, he sponsored one of the first bills in legislature promoting the cause.2 While much has been said about Daley’s motivation in providing Chicago’s working class youth with access to higher education, his truer motivation lie in the political and economic calculations associated with situating a major state university near the city’s central business district. A University of Illinois campus in the city, it was figured, would act as a major economic anchor in the age of deindustrialization and capital flight. If that campus could be located on the border of downtown Chicago, it was also figured, then it could act as a physical barrier to the “slum” areas that were surrounding downtown- especially the expanding Black Belt to the south- thus making it more attractive to both downtown office workers and suburban shoppers.

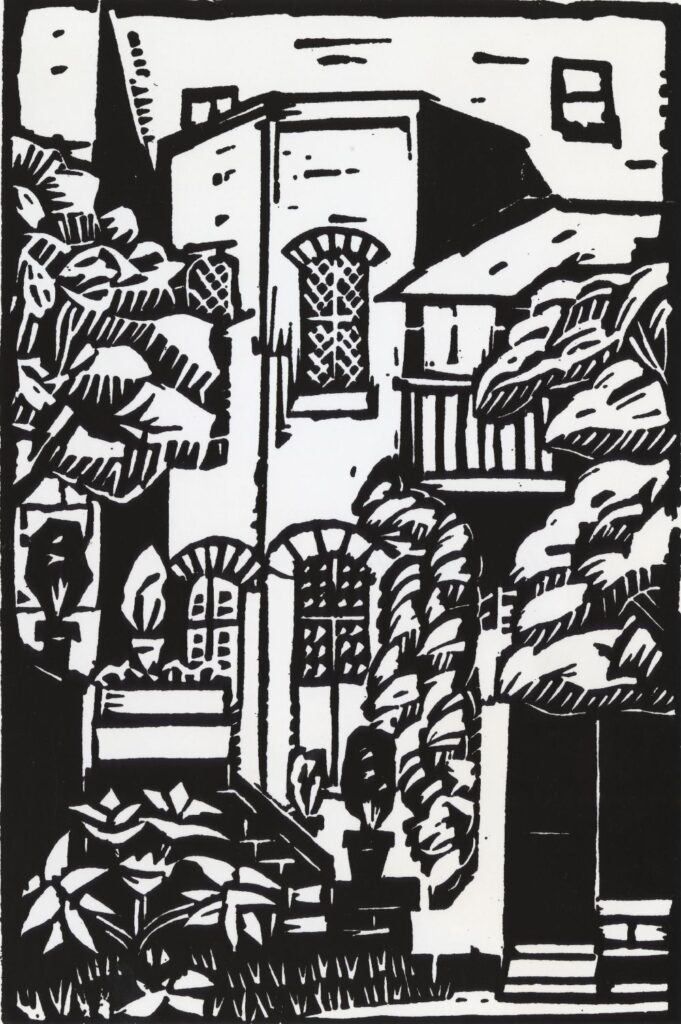

On a nearly parallel track to Daley’s work in securing a University of Illinois campus in Chicago, residents of the “slum” Near West Side neighborhood, who recognized the reality of poverty and its symptoms in their neighborhood but who nonetheless deeply loved and cared for their community, had organized the Near West Side Planning Board (NWSPB) in an attempt to democratically engage with urban renewal policies that they saw demolishing neighborhoods similar to theirs.3 For thirteen years the NWSPB painstakingly organized the neighborhood- a task of phenomenal complication due to the great diversity of the Near West Side- while conducting years-long research projects to formulate a plan for redeveloping the neighborhood in a way that would benefit the entire community.4

Despite the Near West Side community’s powerful display of democratic engagement and the unprecedented opportunity for an American city to redevelop in accord with community-control, the interests of racial capitalism proved to be overwhelming. When it became too expensive to acquire the rail-yard that occupied the land immediately south of downtown that Daley favored as the site for the campus, the fifty-five acre “Harrison-Halsted” tract of land on the Near West Side became a politically convenient option as it was already owned by the city and had been slated for redevelopment (in coordination with the NSWPB).

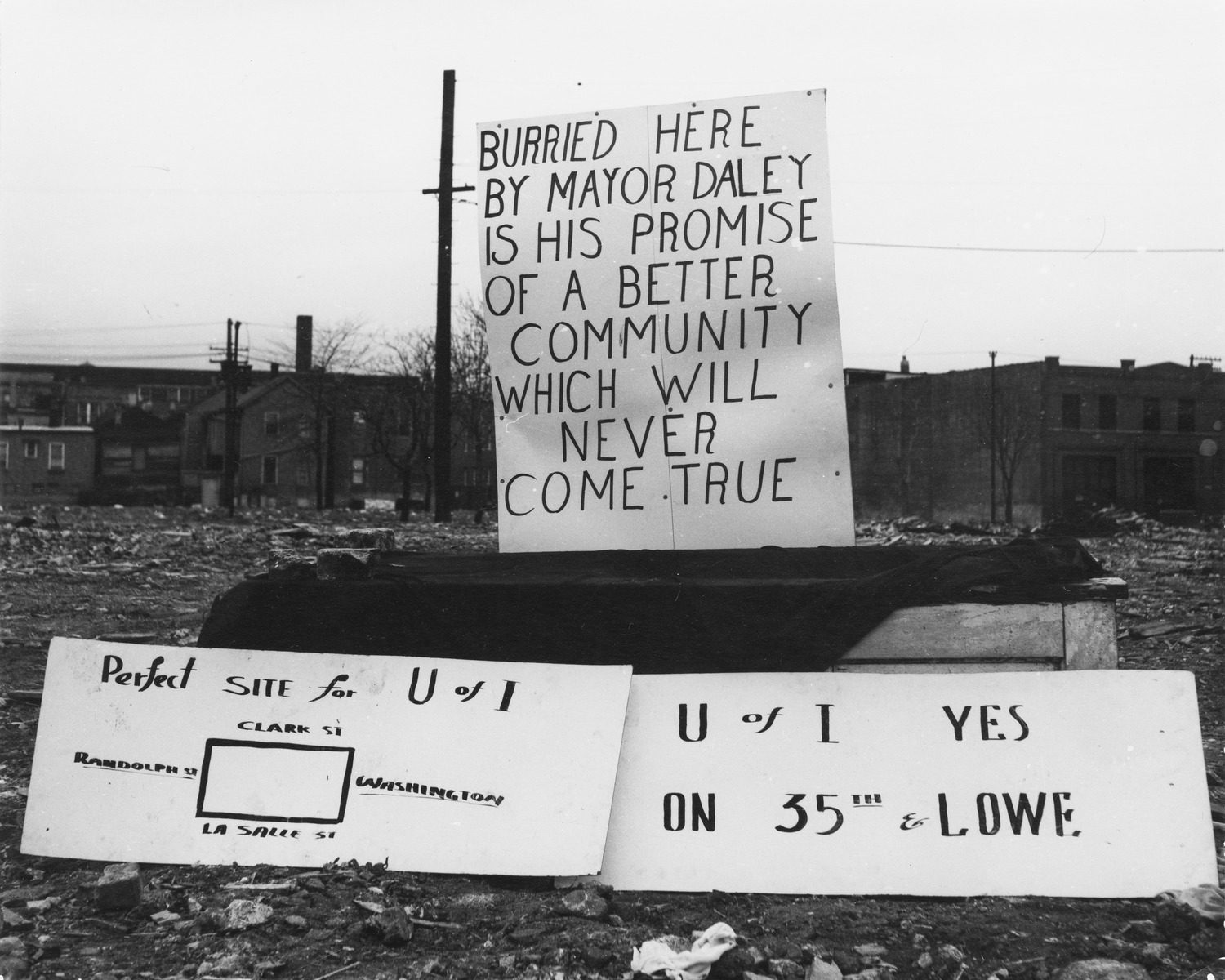

Thus, under the guise of political officialdom, in the broad light of day, the Harrison-Halsted site was offered by Daley to the University of Illinois like it was his to give; like the some twelve-thousand people who lived there weren’t to be dispossessed of their homes and forcefully relocated; like the thirteen years of organizing and planning by the NWSPB meant nothing; like the residents of the Near West Side had no right to place.

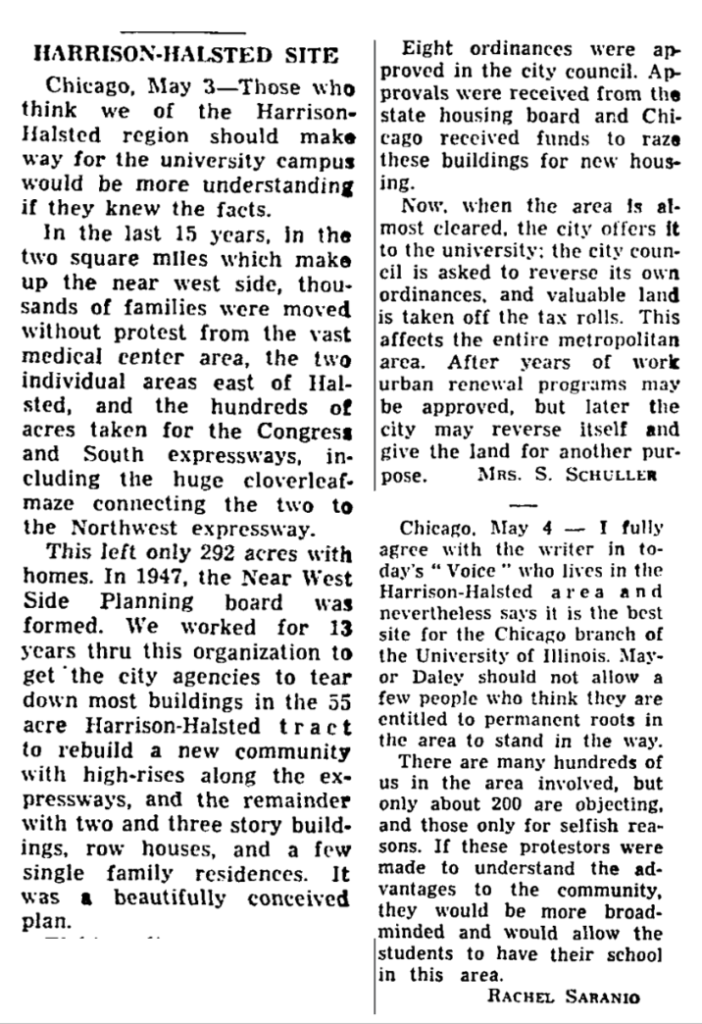

In May of 1961, just months after the official announcement that the University of Illinois had accepted the Harrison-Halsted site from the City of Chicago for the construction of its expansion campus, two members of the Near West Side community wrote contrasting opinion pieces in the Chicago Tribune which highlight many of the fundamental themes and arguments that shaped the debate surrounding UIC’s construction.

The letter from Mrs. S. Schuller reflects one of the most essential themes in the history of UIC’s development- the betrayal of the Near West Side Planning Board by the City of Chicago in their offering of the Harrison-Halsted site to the University of Illinois after more than a decade of seemingly goodwill collaboration between the two parties. Mrs. Schuller gives a concise background on the nature of this betrayal, but more importantly she sheds light on the great feelings of hope and democratic fervor that informed resident participation in the NWSPB. Much of the devastation caused by the betrayal- beyond that caused by the literal dispossession and demolition of the community- was based in many resident’s disillusionment with a political system in which they had previously trusted. For roughly a decade Near West Siders (through the NWSPB) were pioneering community-controlled neighborhood redevelopment and had conceived, formulated, and executed a process of grassroots, participatory urban planning. These folks believed in this plan, and they worked earnestly and painstakingly to construct a plan which would benefit the current residents as opposed to private interests; as Mrs. Schuller reflects “it was a beautifully conceived plan”.

What’s left unsaid by Mrs. Schuller, however, is as revealing as what was.

What Mrs. Schuller failed to mention, or perhaps wasn’t even aware of, is the fact that the work to designate the 55 acre Harrison-Halsted tract as blighted was itself problematic; and revealed the varying levels of “right to place” that existed within the Near West Side community itself. The Harrison-Halsted tract was home to Chicago’s largest and most visible Mexican community, as well as Puerto Ricans, African Americans, and the area’s lower-income first-generation Europeans. In 1954, just prior to the beginning of demolition in the neighborhood, the Near West Side Mexican community fell under siege by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) “Operation Wetback”, which aimed to arrest and deport 35,000 Mexicans from the city.5 In practice, dragnet raids were carried out within Mexican neighborhoods-especially the Near West Side- indiscriminately arresting, detaining, and deporting Mexicans en masse. Just years before much of this community was literally abducted and deported, representatives of the adjacent Italian community concentrated west of Racine Avenue became untrusting of the NWSPB’s ability to protect their homes from demolition and quit the board. Working with a local alderman who famously promised that “there would be no Negroes and no Mexicans living in the new community”,6 the west of Racine group worked to pass a city ordinance that would change the designation of their area from “slum” in need of clearance to a “conservation area”. In effect, this all but guaranteed that the area east of Racine would be demolished.

In its essence, Mrs. Schuller’s letter reflects the layered and often contradictory ideologies and plans that guided the redevelopment of the Near West Side. Where Mrs. Schuller’s “beautifully conceived plan” for the “slum” Harrison-Halsted tract was ultimately politically dominated by the Daley machine, the plan itself was conceived out of a certain political dominance of the Mexican community who was caught in a simultaneous struggle against the INS.

Providing even more insight to the layered struggle for right to place on the Near West Side is Rachel Saranio’s letter in support of UIC’s construction at the Harrison-Halsted site. Two of the essential arguments made in favor of UIC’s construction at Harrison-Halsted are reflected in Saranio’s letter. First is an argument centered around the idea that because of the area’s history as a transient port-of-entry for immigrants, no person or group ought to claim the Near West Side as their own neighborhood- Saranio calls resident’s wish to remain in their neighborhood “entitlement”. Though this argument is actually self-defeating- if one were to follow this argument to its logical conclusion it would mean that all non-Native-American Chicagoans, probably Rachel Saranio themself, ought not be able to claim a genuine right to their neighborhood- this nonetheless was an idea that undergirded significant public support for UIC’s construction. The second essential argument is that the university was a public good that would bring an incalculable benefit to the city. Saranio believed that if Near West Side residents protesting their displacement could only understand the great benefits of higher education then they would surely end their fight. This was a common position that proponents of UIC’s construction repeated for years in the debate against the Harrison-Halsted Community Group that was established to protest and legally challenge UIC’s construction at the Harrison-Halsted site.

The legacy of this line of reasoning still resonates today and is one which must be reckoned with as UIC is more and more often lauded as a public good unparalleled in the city. There is something to be said about this, as UIC has historically served a large minority and working-class demographic, providing thousands of kids an opportunity for upward mobility that they might not have had otherwise. It’s now one of the city’s largest institutions and plays an unquestionably unique and important role in many areas of life in Chicago. This fact must be constantly weighed against UIC’s legacy of displacement, which continues to this day as the university has persistently expanded; as well as against the university’s contradictory status as a tax-exempt non-profit which is also a massive employer and landholder.

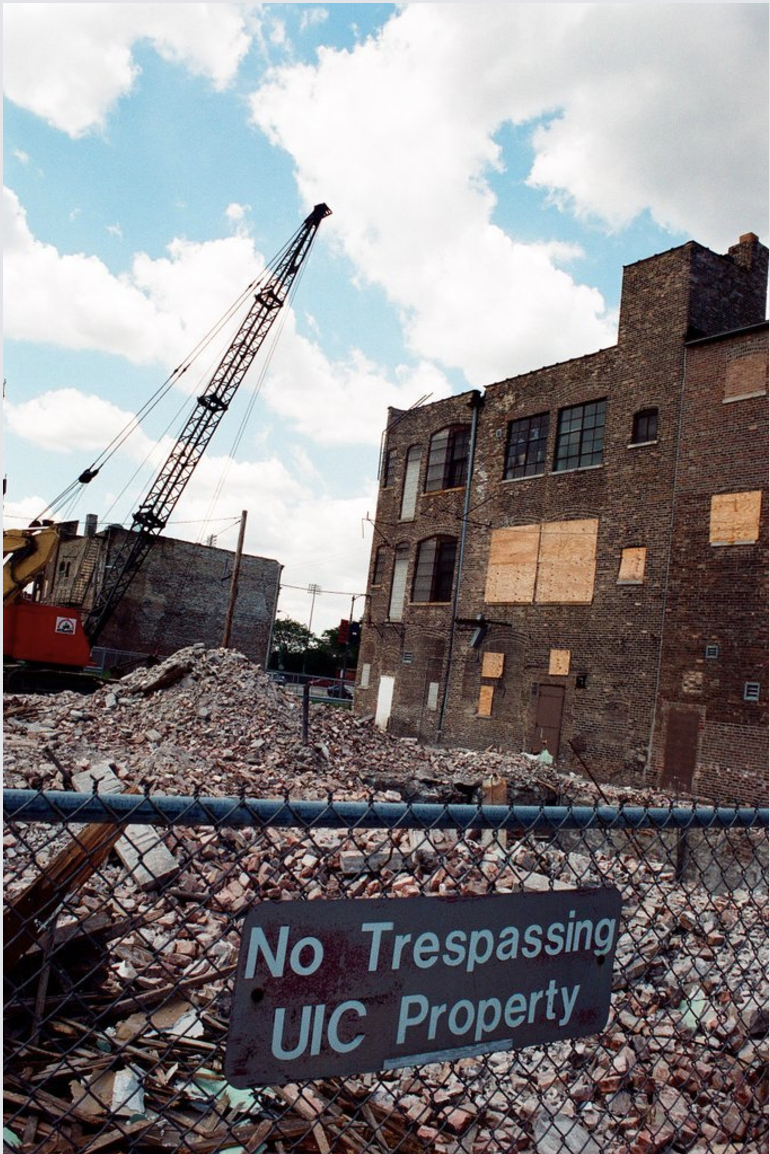

What remains of the old Near West Side now sits awkwardly in the shadow of UIC’s 28-story University Hall; within the grips of a superhighway interchange; blotched with city-owned vacant lots where thousands used to live in public housing; vacant lots owned by the university who awaits the land’s rise in exchange-value. Blue Island Avenue, one of the area’s oldest roads and once the diagonal artery of the Near West Side, now leans beheaded at Roosevelt Road. This is a legacy that reveals much about the relationship between power and place; a demonstration of political and economic dominance that speaks to the ability of vested interests to shape the lives and futures of less-powerful communities.

As an institution that prides itself on a mission to “provide access to educational, research, and clinical excellence, and to create knowledge that transforms the world”, UIC must begin to reckon with its legacy of displacement and work to redress its past harms in a meaningful way.

- Eastwood, Carolyn. Near West Side Stories : Struggles for Community in Chicago’s Maxwell Street Neighborhood. 1st ed. Chicago: Lake Claremont Press. 2022 166 ↩︎

- Cohen, Adam (Adam Seth), and Elizabeth (Elizabeth Joel) Taylor. American Pharaoh : Mayor Richard J. Daley : His Battle for Chicago and the Nation. First edition. Boston: Little, Brown, 2000. 224 ↩︎

- Sorrentino, Anthony. Organizing against Crime : Redeveloping the Neighborhood. New York: Human Sciences Press, 1977. 205-230 ↩︎

- Johnson, P. B. (Paul B.), Hull House Association., and the Near West Side Planning Board. Citizen Participation in Urban Renewal; the History of the Near West Side Planning Board and a Citizen Participation Project Sponsored by Hull-House Association. Chicago: Hull-House Association, 1960. ↩︎

- Amezcua, Mike. “Deportation and Demolition.” In Making Mexican Chicago. University of Chicago Press, 2022. 36-46 ↩︎

- Amezcua, “Deportation and Demolition”. 48 ↩︎